- Karachay folk music

- Special tunes

- The classes of Karachay folk music

- Class 1: Rotating and plagal motion (№ 1−8)

- Class 2: One or two short lines and their variations with x(1)1 cadences (№ 9-37)

- Class 3: Four short lines with (1) main cadence (№ 38-53)

- Class 4: Four short lines with the first line ending on the key note, with a (pseudo) domed structure and 1(x)y cadences (№ 54−62)

- Class 5: Four short lines with (VII) main cadence (№ 63−70)

- Class 6: Four short lines with (2) and (b3) main cadences (№ 71−105)

- Class 7: Four short lines with (4/5) main cadences (№ 106−115)

- Class 8: Four short lines with (4/5) main cadence and a higher beginning (№ 116−138)

- Class 9: Four short lines with (7/8) main cadences (№ 139−145)

- Class 10: One- or two-lined tripodic tunes (№ 146–186)

- Class 11: Tunes with four tripodic lines (№ 187–199)

- Class 12: Jir tunes (№ 200–278)

- Class 13: Four long lines with arched (domed) structure (№ 279–287)

- Connections between Hungarian and Karachay folk music

Picture 5. Balkar young man from Ogari Malkar village (Caucasus Mountains)

Connections between Hungarian and Karachay folk music

Historical data permit to seek for genetic connections between certain strata of Hungarian and Karachay folk music, and indeed, several Karachay tunes have convincing or sometimes more remote Hungarian analogies. In addition to the similarities of melodic outlines, there are other correlations between the two folk musics, too. Let us first take a closer look at these.

Scales. The most frequent scales (63%) are the ones with minor third (b3), overwhelmingly the Aeolian (54%), far less Phrygian (6%) and Dorian (3%). Out of the scales of a major character (35%) the Mixolydian mode is predominant. This distribution more or less tallies with the Hungarian, although there is a smaller rate in major-character tunes in Hungarian folk music. The highly complex Karachay ethnogenesis would make pentatonic scales quite probable, since in addition of multifaceted Caucasian and Iranian groups, diverse Turkic people also contributed to their ethnogenesis. It is known, however, that not all Turkic groups have pentatonic music. Unlike some layers of Hungarian folk music which are distinctly pentatonic, there are hardly any Karachay tunes moving on a pentatonic scale. Pentatonic phrases or turns may at most be heard at the head or the end of a line, e.g. G,-C-D, G-E-D, E-D-C-A, A-D-C-G, at the beginning, G-E-D-C at the end of a tune, E-C-A, C-G,-A, G’-E-C and D-G, or D-A at the end of some lines. From the scale of some tunes the 2nd degree is missing (e.g. № 202, 204, 227), but degree 6 is practically always present.

Form. In Karachay music I have found merely nine single-core tunes and three tunes that comprise three different musical ideas. This music is fundamentally predominated by two- and four-core structures, with a diversity of subgroups. In the classification songs of two long divisible lines are taken for forms of four short lines, and the refrains are ignored. Tunes whose second line terminates on the base note and is followed by a plain narrow-range line ending on the base note again are taken for two-lined tunes in most cases.

Among two-core tunes the AB form is salient (13%), and four or five items of the following schemes can be found each: AAAB, ABvAB, ABBB or AB + refrain. This is all familiar to Hungarian folk music, with the AAAB form being rare. (A marks a line that closes on the same degree as A, its melody outline is similar, but it moves below A.)

By far the most populous group is that of tunes with four independent melodic lines (55%) with highly diverse but predominantly descending cadential sequences. This also parallels the Hungarian case today. The most frequent ABCD (34%) form plays an important role in both Karachay and Hungarian folk music. Considerable Karachay forms are also ABc/AB and AB/AC (9%), ABBC (1.4%) and AB/CB (2%) mostly of more archaic strata, but these forms are not frequent in Hungarian folk music. AA(v)BC (9%) is also found in a lot of tunes, but they are mainly of art music origin.

Several four-lined tunes include consecutive seconds and thirds, there are two or three A2BAC and A3B3AB structure, whereas there is practically no line parallelism in two-lined, two-core tunes.

Of special interest are the parallel lines at a distance of a fourth or fifth, a typical feature of a stratum of Hungarian folk music. In Karachay folk music AB4/5CB (5%) and AB4/5AB (4%) forms are relatively frequent, the second and fourth lines progressing in parallel forths or fifths. It is not infrequent with Hungarian fifth-shifting tunes either that lines 1 and 3 are less similar than lines 2 and 4.

The forms A4B4AB (2 tunes), A5A5A2A (1) and many A5B5AB (4) and

A5A5BA (3) resemble more closely the Hungarian fifth-shifting forms. A comparison between these Karachay tunes and the Hungarian pentatonic fifth-shifting songs will clearly reveal, however, that the similarity does not necessarily imply genetic identity. What we have in Karachay folk music is not some short pentatonic twin-bar motif repeated a fourth or fifth lower, but a more or less accidental parallel movements between a higher first and a lower second part (e.g. № 249).

Some four-lined tunes descend along step progression in the form of A4A3A2A, A3A2A2A. Such sequential descent is not infrequent in Anatolian music either. In Hungarian folk music tunes built of sequentially descending lines are partly subsumed in the lament style, but the long lines of these Hungarian tunes considerably deviate musically from the sequentially descending Karachay dance tunes.

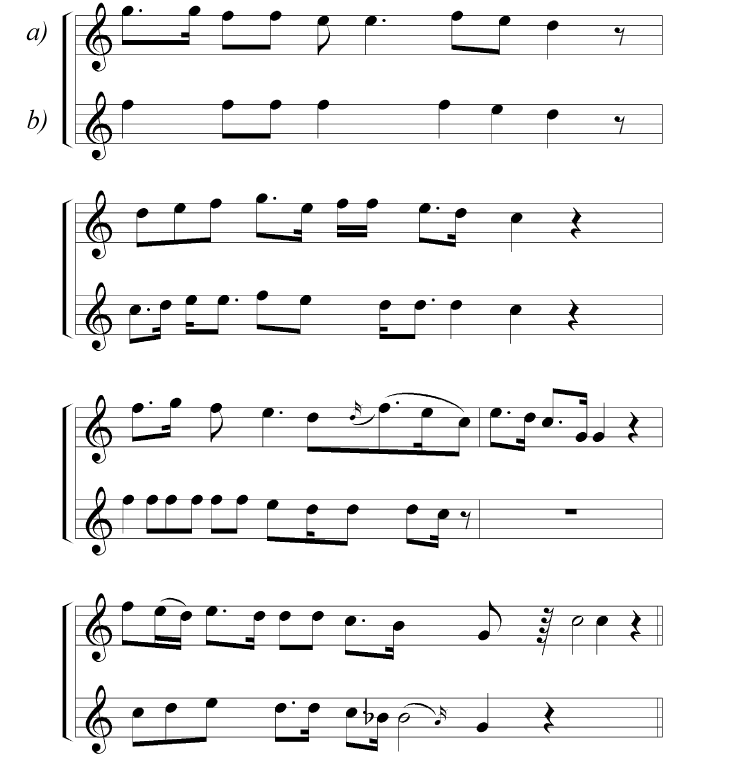

Some recursive, domed structures of AA5A5A character can also be come across, but they are the outcome of some new development possibly attributable to the Soviet period. A more detailed examination would, however, be justified in this field. Ex.14 shows that Hungarian analogies can be found even to a Karachay tune with a specially divided third line. In the indices Hungarian variants comparable to the other domed Karachay tunes are also given.

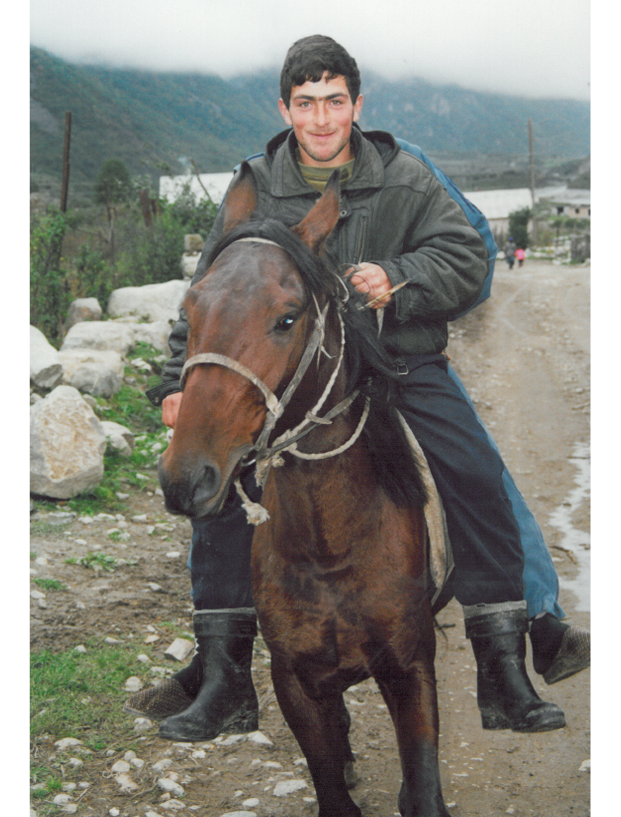

Ex.14. Domed tune a) Karachay tune (№ 281) and b) a Hungarian new-style analogy

Compass. The typical tonal range of Karachay tunes is seven-eight notes, and since unlike the Hungarian songs, they do not sink below the base note, the most frequent ambitus is 1-7/8 (26%). It is followed by four relatively large compass groups: 1-7 (16%), 1-6 (15%), 1-5 (12%), 1-9 (10%) and four smaller ones: 1-10 (3%), 1-b9 (2.5%), 1-4 (2%) and 1-#6 (1.5%). A single tune was found with the narrowest 1-3 and one with the widest 1-11 ranges. On the whole, this is quite similar to the Hungarian picture.

Tunes declining below the base note often have other singular features as well: the majority are plagal falling-rising tunes. Sometimes the extension of the compass is caused by a leap down to the Vth degree, which is rare in Hungarian music. Degree VII at the end of a Karachay melody line is rare but not exceptional (4%), among the ranges reaching down below the base note only VII-5 is noteworthy (3%).

Metre. Both ethnic groups tend to perform their more archaic tunes in parlando-rubato manner (Karachay: 42%!); as for the giusto performance, 2/4 and 4/4 time (44% of Karachay tunes) are characteristic, with 6/8 meter also occurring among the Karachay tunes (5%). The latter people have hardly any asymmetrical rhythms, most frequently 5/8 in some religious zikir tunes (5%). That also more or less corresponds to Hungarian folk music in general. In Karachay folk music we do not hear the asymmetrical triple division of 3+2+2 for 7/8 time or 3+2+3 for 8/8, which are relatively frequent in Hungarian music.

Rhythmic formulae. There are saliently many +>&@, +>

+ and +>+>&@ patterns, which are also the most important rhythmic formulae of Hungarian folk music. Some other patterns of relative significance in Hungarian folk music, too, include +>@ @., +@ @ > +$ and ++>+$ as well as @ @>&@.

Similarities by melody outline

A brief digression is required before a comparison of melodic outlines is to be attempted: When can two melodies be regarded as similar? When one takes a closer look at a Hungarian folk music stratum, class or style, one finds that it may contain widely diverse tunes in several regards. When, for example the force of coherence in a melody class is the similarity of melody contours, tunes of different meter, rhythm, structure, etc. may be included. Yet, when the overall outline of the melody and the important stylistic features are similar and between compared tunes a link can be built of a series very similar tunes or the studied melodies can be retraced to a common musical idea, the two tunes can rightly be regarded as relatives or stylistically similar.

The analysis of Hungarian folk music is highly advanced, and most tunes can now be ranged in one or another class. When we compare the Hungarian music with tunes of a basically similar but in several regards different musical system, the compared tunes may shed new light on the Hungarian classification as well. For instance, in both Karachay and Hungarian folk music descending four-lined tunes constitute a fundamental layer. Yet despite the great similarity of the melody contour, the Hungarian four-liners appear unfamiliar to a Karachay ear, and vice versa, because some musical turns, the degree of pentatonization, the rhythm, etc. are unusual or different.

Here, I regard two tunes – be they Hungarian or Karachay – as similar when the pitch levels of their lines, the characteristics of the melody progression and the nature of their scales are similar. I disregard now the subtle differences of melody contours, even though that would be the basis of a deeper analysis. Many of the resultant Karachay − Hungarian analogies are fairly close by virtue of their structure, rhythm and melodic turns in addition to the general melody outlines. I do not risk using the term genetic similarity because there isn’t and cannot be proof of it.

Similarities between Anatolian and Hungarian musical styles and strata have often been mentioned. Let us remember that the folk music of Anatolia is highly complex owing to the intricate ethnogenesis, the large population and the vast area. A wide variety of musical forms and schemes can be found there from the simplest to the most advanced. Some central Anatolian styles have stylistic analogies in Hungarian folk music. Karachay folk music is somewhat less complex than the Anatolian, with the simplest and most complicated tunes missing, the two- or four-lined forms of an octave range being predominant, and this in broad outlines compares it to the present-day state of Hungarian folk music.

Looking at the Karachay – Hungarian melodic parallels, I first consider the broader strata. Large numbers of similar tunes can be found in both stocks, often suggestive of deeper connections. This is followed by the brief presentation of sporadic or less certain analogies.

As seen earlier, the following blocks of Karachay folk tunes have been differentiated:

|

1. |

Rotating and plagal motion |

* |

|

2. |

One or two short lines and their variants, with (2) main cadence in group 2.2 |

* |

|

3. |

Four short lines with (1) main cadence |

|

|

4. |

Four short lines with line 1 closing on the key note, domed or pseudo-domed structure and 1(x)y cadences |

* |

|

5. |

Four short lines with 1(VII)x cadences |

|

|

6. |

Four short lines with (2) and (b3) main cadences |

** |

|

7. |

Four short lines with (4/5) main cadences |

|

|

8. |

Four short lines with (4/5) main cadences and a higher start |

|

|

9. |

Four short lines with (7/8) main cadences |

|

|

10. |

Tripodic tunes with one or two lines |

** |

|

11. |

Tripodic tunes of four lines |

** |

|

12. |

Jir tunes of special structure |

* |

|

13. |

Four long lines in recursive (domed) structure |

** |

* marks a more distant, ** mark a closer relationship between a Hungarian and Karachay musical class or group.

Let us go through the Karachay classes that can be compared to Hungarian analogies convincingly.

Class 1. Tunes of rotating or plagal motion

Zoltán Kodály (1937–76:54) noted: “The endless repetition of twin-bars or short motifs in general is a typical form in the music of every primitive people, and even in the ancient traditions of more advanced nations.” In contemporary Karachay folk music, that only applies to a part of the instrumental repertoire at most, because in my collection of a total of 1200 tunes a mere two tunes of twin-bar character can be found: one consisting of a motif skipping on the A-E, bichord, the other (Ex.15) rotating round the middle A note of the B-A-G trichord. The latter is one of the chief types of Hungarian and Anatolian children’s ditties and of the rain-making tunes. Hungarians also sing their incantations of warmth, plenty or rain on the motif rotating on E-D-C-D (= B-A-G-A), sometimes waving green leafy branches. Kiszehajtás [chasing away winter] has an exact musical and customary counterpart in Anatolia, among other places. Among the Karachays, the genre of these kind of tune is rain-magic, too. It is noteworthy that similarly to the Azeris, Turks or Kazakhs, some tunes of the recitation of the Quran also move on the E-D-C trichord and end on D. The other typical motif of Hungarian children’s games, D-E-D-B often extended to become a major hexachord downward cannot be found in Karachay folk music. NB. The rotating E-D-C-D and D-E-D-B rotating motifs of Hungarian children’s songs do not appear in the folk music of Finno-Ugrians although their music is characterized by twin bars.

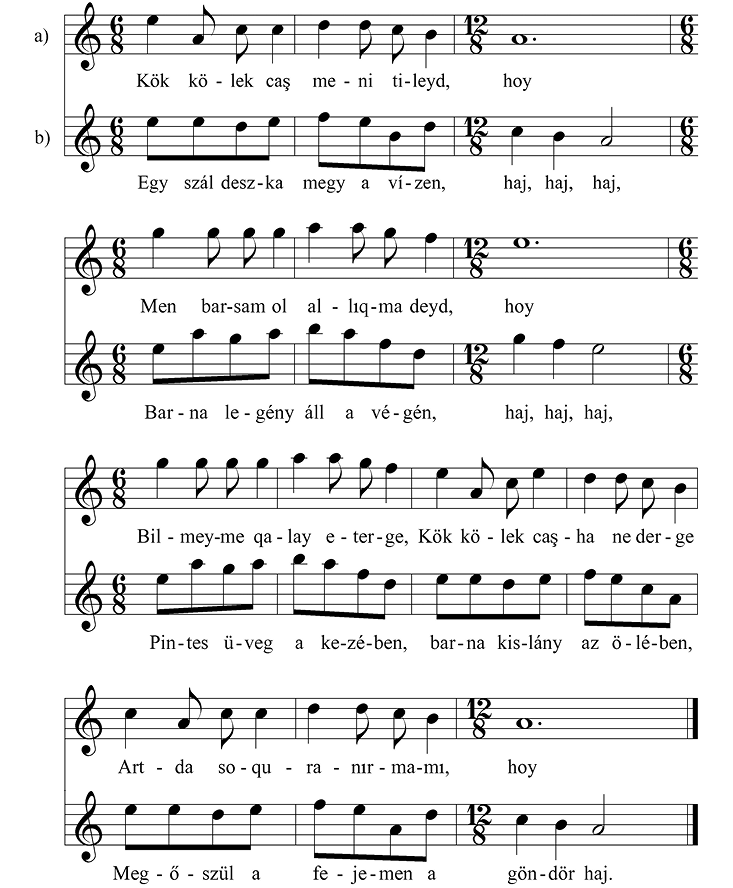

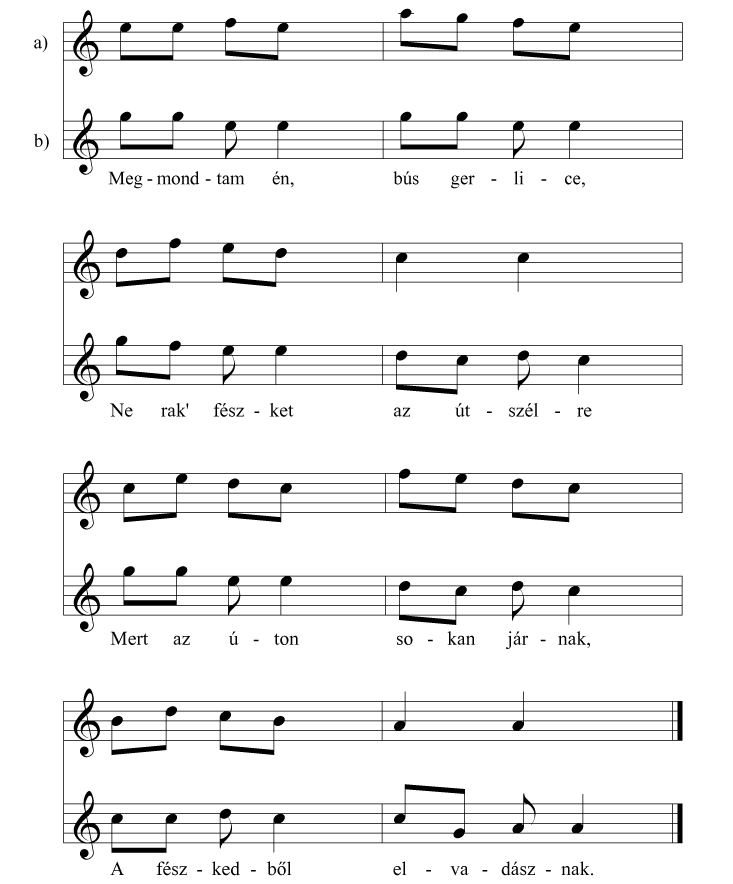

Ex.15. a) rotating Karachay tune (№ 1), b) Hungarian children’s song (Magyar Népzene Tára I: № 77)

Apart from twin-bar tunes, there are plagal melodies of rising-falling motion in Class 1. The Hungarian regös tunes are of this kind whose origins and relations have been among the moot questions of folk music research since the turn of the 20th century. Many see it as the remnant of shamanic ceremonies which absorbed Byzantine, Slavic and Caucasian (!) influences before the arrival of the Magyars in the Carpathian Basin. The discussed Karachay tunes, similarly to the Hungarian regös tunes, are alien among the basically descending old style tunes, but their texts in both folklores allude to archaic traditions, several genres being linked to rain-making, lullabies, or natural religion. This musical form refers back to ancient traditions and is represented by few tunes. Though the Karachay tunes lack the trance-inducing magic refrain formula ’Hej, regö, rejtem/rajta’ or ’dehó-reme-róma’, they also have repetitive refrains. In addition to general structural similarities, the Karachay falling-rising tunes display close kinship to the Hungarian regös tune type (Ex.1).

Class 2. Group 2.2: Two short lines and their variants with (2) main cadence

Eight of the tunes built of two short lines have (2) for their main cadence and all use a narrow gamut (1–4/5) of major character. In this way they display formal similarities with the small form of the Hungarian diatonic laments, but compared to their free performing style and variable, improvisatory lines most of them are dance tunes of short lines performed giusto.17 Some performed in diminished rhythm do resemble sections of Hungarian laments (Ex.2.2). Later, in groups 6 and 10.3 Karachay forms closer to Hungarian laments will also be seen.

Class 4: Four short lines in an ascending structure with 1 (x) y cadences

In these tunes a lower first and fourth lines flank a higher second and a partly higher third lines. The typical scheme is AvB/AC, the first and third lines being identical, or at least similar, and the second being high. Despite their ascending start these Karachay tunes can be ranged with the older strata, but they are not in kinship with the domed structure of the Hungarian new-style tunes (№ 62).

Class 6: Four descending lines with (2) and (b3) main cadences

This class includes four-lined tunes descending evenly on Aeolian-Phrygian scales, starting with a high register and ending lower, with the internal lines moving in mid-range. Two tune types emerge markedly from this set. One appears to be more recent, with step progression in its lines. Hungarian scholarship regards some sequentially descending tunes as the recent descendants of laments, but these differ from the Karachay tunes in question along their essential features.

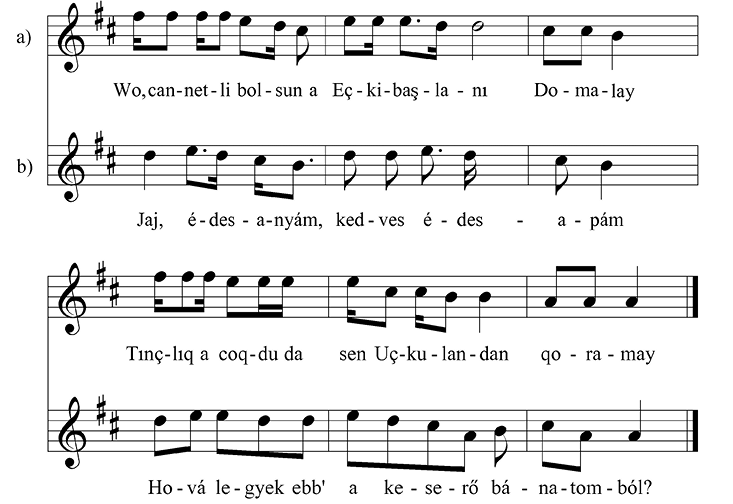

The structure of the other tune type is more balanced, more dignified so to speak. The first line moves high and ends on degree 4 or 5. Lines 2 and 3 are often similar and basically move on E-D-C and close on C (the end of line 3 being more varied). Line 4 descends from degrees 5-7 to the fundamental. Those with 5(b3)1 cadences resemble a bit less, those with 5(b3)b3 cadences resemble more the Hungarian-Anatolian psalmodic and descending tunes, those in Anatolia more markedly.18 This melody outline characterizes several Karachay tunes and a multitude of such tunes and their more advanced variants can be found in Azeri, Anatolian, Kazakh or Hungarian folk music. As for the Hungarian tunes, despite the general similarity, they are differentiated by their pentatonic character (Sipos 2000). Some of the pertinent Karachay tunes are religious zikirs, there are many lullabies, too, which suggests that it is a more archaic form which was incorporated later in the religious repertory (Ex.16).

Ex.16. a) psalmodic Karachay tune (№ 96) and b) its Hungarian analogy (Dobszay–Szendrei 1988: № 46a)

Class 10: One- and two-lined tripodic tunes

In the large group 10.3 of Class 10 there are major-character tunes with (2) main cadence. With their free performing style, the improvisatory shaping of the lines and the descending melody contour they do conjure up the realm of Hungarian and Anatolian laments. The tunes descending on a major hexachord and cadencing on B and A (transposed to A) are part of a broad rubato musical style that also includes heroic songs. The most frequent form has tunes with lines cadencing on neighboring notes, but some tunes have lines sinking to the key note or some with lines ending higher (Ex.17).

Ex.17. a) lamenting Karachay tune (№ 170) and b) its Hungarian parallel (MNT V:№ 41 lines 4-6)

Apart from similarities, there are differences from Hungarian laments displayed by several tunes in the class. Such are the leap down to the fifth below the closing note, the B-#G-A line ending and the giusto performance of pairs of lines.

Melody lines may extend in the direction (A-G)-F-E-C→ B-G, downward. Extension downward also occurs in Hungarian and Anatolian laments, mostly in the forms F-D-C→bB-A, and F-D-C→bB-A-G,. A spectacular example of the Karachay extension downward is a type of Karachay style whose first lines descend from G to D or C as is customary in laments, but their third and fourth lines jump to the lower so and close on C (Ex.18).

Ex.18. Parallel laments a) Karachay lament,

b) Hungarian lament (Dobszay 1983, 29/d)

There is an even larger divergence from the central two-core laments when the line undulating down to C is followed by a line sinking to G,. Hungarian analogies can be found, but while the Karachay lament is fitted snugly into the voluminous group of Mixolydian Karachay tunes, in the Hungarian stock there are relatively few Mixolydian tunes.

The Karachay lament in Ex.10.5b was sung without words by a woman active as a wedding musician. It is symptomatic that she was only willing to do so when the local people, mainly the men, were sent out of the room. From the reactions of the remaining women and the plaintive mood that overcame them during the song it could be inferred that the lament was authentic. The lament tune sung more than once descended basically on parts of the pentatonic Aʼ-♯F-E-D-B-A, scale, touching on the G note at unaccented places at most. It has a two-lined variant in which the do-pentatonic descent of the first line is responded to by the sol-pentatonic descent in line 2. It is ample food for thought that in this distinctly non-pentatonic melodic world it is the lament of all genres that has a scale of pentatonic character.

Class 11: Four-lined tripodic tunes

It is easy to find Hungarian analogies to the popular tripodic tunes with 5(b3)b3/4 cadences in group 11.1. Lines 3 and 4 are the fourth-fifth-shift variants of lines 1 and 2, resp. (Ex.11.1).

Class 12: Jir tunes of special structure

In some groups of Class 12 tunes with 1(4/5)1 cadences occur that have low first and fourth lines and higher inner lines. In some of these tunes line one descends to the key note in the middle, in others the first line is descending or hill-shaped. As their AB/AC or AB5AB structure confirms, they are not in kinship with the Hungarian domed tunes just like the tunes in Class 4, or with the domed tunes in Class 13. Although the cadence of line 2 is often (5), line 3 is often the variant of line 1 or it sinks deep even if it is different from line 1 (e.g. № 211).

Class 13: Four long lines with recursive (domed) structure

Finally, let us see a few Karachay tunes whose domed structure would suggest that they are of a more recent style and indeed, they display close relationship with some Hungarian new-style songs. When I spoke about the analogies of form, such a Karachay tune and its Hungarian parallel were already shown (Ex.1).

Further parallels and summary

In many cases the Hungarian and Karachay parallelism is not between tune groups but is more sporadic; to present these would widely exceed the purview of this book. It is, however, informative to cite some statistics.

One third of the 357 Karachay tunes, which constitute a representative sample of the whole collection, can be paired with Hungarian analogies, sometimes more than one to a Karachay tune. That means that 240 Hungarian parallel tunes can be added to the studied Karachay tunes. About half the analogies are convincing, the rest showing similar melody progression in other modes or are more distant parallels.

That shows a close musical connection between the Hungarian and Karachay folk music stocks, but that does not mean at all identity. Yet such a large degree of similarity in melody outlines, modes, rhythmic patterns, etc. is thought-provoking. Furthermore, if the ancestors of these two sets of tunes had once been closer to one another, they would certainly have diverged at least as widely as they are now during the millennium that has passed since.

Between the Karachay and Hungarian children’s tunes some closer similarities can be found apart from a broad stylistic identity. The Karachay-Balkar psalmodic, descending and lamenting tunes belong to the Bartókian primeval “style race” to which the pertinent tunes of Bulgarian, Slovakian, Romanian and some other people’s tunes belong. Though there are typical ethnic and areal differences within a general stylistic identity, the similarities of individual phenomena and melody construction encourage scholars to continue researching a broadly interpreted common origin or at least some closer musical connections. Such tunes cannot be found in the music of every ethnic group; e.g. the Finno-Ugrian people have no such tunes except perhaps for the laments, and the repertoires of different Turkic groups also mostly contain one or the other. It cannot be explained convincingly as yet why all three tune types mentioned above can be found in the music of the Anatolian Turks, and in such great quantities, too.

To be able to draw further conclusions, it would be important to have an insight into the music of the neighbors of the Karachays, first of all the Ossetians, Kabards and Cherkesses, as at first glance too, there are several similar musical strata in the music of these groups and the music of the Karachay-Balkars. The most important and most wide-spread Karachay-Balkar jir tune class has several Kabard analogies in addition to Hungarian parallels, although the Kabards probably have nothing to do with the Hungarian ethnogenesis apart from their name.

At any rate, the present research has confirmed that the music of no ethnic group can be handled in isolation, but the comparative examination of the culture of groups living over vast areas is necessary.

Picture 6. Two Karachay men from Ogari Malkar village

Table of Hungarian-Karachay tune parallels

Next to the identifier of a tune I list the convincing Hungarian parallels, e.g. 16-087-0-1 alludes to that tune type in the Dobszay–Szendrei (1988) system of folk music types. In addition to the listed tunes there are several that more or less resemble the Karachay tunes.

In the list I indicate the Hungarian analogies. The Hungarian tunes can be looked up in Dobszay–Szendrei (1988), and at www.nepzeneipeldatar.hu. I also refer to the tunes in Dobszay–Szendrei (1988) with the number they bear in the book, too (e.g. III/139).

Parallels to Karachay tunes can be found in the following Hungarian tune groups:

Tunes descending from the octave

Descending fifth-shifting pentatonic tunes

Bagpipe-swineherd merry-making style

|

Karachay tune |

Hungarian analogy |

|

Examples |

|

|

1. |

Regös tunes |

|

2.3a |

10-46-1 (III/158) – archaic small-ranged tunes, 18-162 (I/17) – psalmodic tunes |

|

2.3b |

15-27 (IV/349)19 – fifth-shifting |

|

2.4a |

18-86 – shepherd’s song |

|

3.1. |

18-162 (I/17) – psalmodic, 18-414 (III/100) – archaic small-ranged tune |

|

3.2. |

18-415 (III/139 with augm. sec.) – archaic small-ranged, |

|

3.3a |

18-466 (IV/42) – new-style small ambitus tunes |

|

3.3b |

18-235 – bagpipe-swineherd songs |

|

4.2. |

18-526-1 (IV/189) – new-style narrow gamut tunes |

|

6.3. |

18-499-1-0 (IV/86) – new-style narrow gamut tunes |

|

6.5. |

17-50-0-1 (I/24) – psalmodic songs |

|

6.6. |

16-31 – fifth-shifting, 18-52 – fifth-shifting, 18-53 – fifth-shifting |

|

6.7. |

18-140 (I/50) – psalmodic, 18-141 (I/53) – psalmodic, 18-143 (I/54) – psalmodic, 18-77 – shepherd’s tune, 16-46 – fifth-shifting, 16-47-0-1 (I/56) – psalmodic tunes |

|

8.1a |

16-70 (II/40) – bagpipe-swineherd songs |

|

8.2a |

18-302 – rising broad-ranged tunes |

|

10.2. |

15-33 (IV/375) – new-style narrow-ranged, 18-409 (III/96) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

10.5a |

10-22-1 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

10.5b |

11-52-0-1 – bagpipe-swineherd, 12-11-0-1 (II/2-minor char.) – lament tunes |

|

11.1. |

10-8 – fifth-shifting, 12-3 (I/43) – psalmodic tunes |

|

11.3. |

18-198 (II/51) – laments |

|

12.1. |

10-46-2 (III/159) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

12.3b |

12-52-1 – rising broad-ranged tunes |

|

12.5b |

In Hung. folk music 4(5)x can be seen only in 16-37 (art song) |

|

Class 1 |

Rotating or plagal motion |

|

№ 1, 8 |

rotating children’s game song with E-D-C core |

|

№ 2-7 |

some regös tunes |

|

Class 2 |

One of two short lines and variants with x(1)1 cadences |

|

№ 16 |

16-175 (III/49) – archaic small-range tunes |

|

№ 17 |

18-563 (IV/279) – new-style narrow-ranged tunes, 16-175 (III/51) – archaic narrow-ranged songs |

|

№ 24 |

18-162 (I/17) – psalmodic, 18-410 (III/13) – archaic narrow-ranged, 17-115 (III/39)- archaic narrow-ranged |

|

№ 27 |

17-142 (III/86) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 36 |

18-417 (III/124) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 37 |

18-266 (AAAB) – bagpipe-swineherd, 17-70 – bagpipe-swineherd, 19-7 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

Class 3 |

Four short lines with (1) main cadence |

|

№ 42 |

16-216 (III/147) – new-style narrow-ranged, 18-162 (I/17) – psalmodic |

|

№ 44 |

18-234 – bagpipe-swineherd, 18-161-1 (I/6, I/11) – psalmodic, 17-118 (III/22) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 50 |

18-83 – shepherd’s song |

|

№ 52 |

17-57 – bagpipe-swineherd songs |

|

Class 4 |

Four short lines in (pseudo)domed form |

|

№ 59 |

17-93 – ascending wide-ranged tunes |

|

Class 5 |

Four short lines with 1(VII)x cadences |

|

№ 66 |

18-179 (I/20 – three-lined) – psalmodic, 18-163 (I/16) – psalmodic tunes |

|

№ 67 |

18-179 (1/20) – psalmodic, 18-163 (I/16) – psalmodic |

|

№ 70 |

18-232 – bagpipe-swineherd songs |

|

Class 6 |

Four short lines with (2) and (b3) main cadences |

|

№ 72 |

18-456 (IV/31) – new-style narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 75 |

18-456 (IV/31) – new-style narrow-ranged, 16-61 (IV/408) – lament |

|

№ 77 |

18-456 (IV/31) – new-style narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 78 |

16-61 (IV/408) – lament, 16-57 (II/6) – lament |

|

№ 79 |

16-57 (II/6) – lament |

|

№ 82 |

17-130 (III/91) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 84 |

16-120 – rising wide-ranged, 18-157 (I/8) – psalmodic, 18-82-0-1 – shepherd’s song |

|

№ 86 |

18-146 (I/60) – psalmodic, 18-148 (I/59) – psalmodic tunes |

|

№ 87 |

18-146 (I/60) – psalmodic, 18-148 (I/59) – psalmodic, 18-151 (I/58) – psalmodic |

|

№ 92 |

10-46 (III/159-160) – archaic small-ranged, 18-161-0-1 (I/11) – psalmodic, 16-51-0-1 (I/5) – psalmodic |

|

№ 93 |

16-49 (I/47) – psalmodic, 16-51-0-1 (I/5) – psalmodic, 17-51 (I/24) – psalmodic, 18-153 (I/45) – psalmodic tunes |

|

№ 94 |

10-46-1 – archaic narrow-ranged |

|

№ 96 |

18-49 – fifth-shifting, 18-53 – fifth-shifting, 18-54 – fifth-shifting, 18-152 (I/44) – psalmodic, 18-153 (I/45) – psalmodic, 18-154-0-1 (I/46) – psalmodic, 17-51 (II/31) – psalmodic, 17-52-0-1 – psalmodic tunes |

|

№ 97 |

16-29-0-1 – fifth-shifting, 16-31 – fifth-shifting, from 18-48 to 56 – fifth-shifting, 18-152 (I/44) – psalmodic, 18-154 (I/46) – psalmodic |

|

Class 7 |

Four short low lines with (4/5) main cadences |

|

№ 107 |

16-198 (III/82a) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 109 |

18-79 and 80 – shepherd’s song, 18-299 and 301 – rising broad-ranged tunes |

|

№ 111 |

16-198 – archaic narrow-ranged |

|

№ 112 |

18-185-189-193-194 – lament |

|

Class 8 |

Four short lines with (4/5) main cadences and a higher start |

|

№ 116 |

16-70 (II/40) – lament, 16-63 (II/19) – lament, 18-185 (II/23) – archaic narrow-ranged |

|

№ 125 |

18-222 – bagpipe-swineherd, 18-226 – bagpipe-swineherd, 18-231-0-1 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

№ 127 |

16-16 – fifth-shifting, 17-3 – fifth-shifting, 18-3 – fifth-shifting, 18-14 – fifth-shifting, 18-18 – fifth-shifting, 18-20 – fifth-shifting, 18-24 – fifth-shifting, 18-25 – fifth-shifting, 18-71-0-1 – shepherd’s song, 18-72 – shepherd’s song |

|

Class 9 |

Four short lines with (7/8) main cadences |

|

№ 142 |

17-10 – fifth-shifting |

|

№ 144 |

16-16 – fifth-shifting, 11-8-0-1 – fifth-shifting, 12-1 – fifth-shifting, 18-3 – fifth-shifting, 18-14 – fifth-shifting |

|

Class 10 |

One- or two-lined tripodic (archaic) tunes |

|

№ 146 |

11-107 (III/162) – archaic narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 14820 |

11-65-1 – bagpipe-swineherd songs |

|

№ 170 |

13-113 – new narrow-ranged tunes |

|

№ 173 |

16-175 (III/51) – archaic narrow-ranged, 18-563 (IV/279) – new-style narrow-ranged |

|

Class 11 |

Four-lined tripodic tunes |

|

№ 187 |

11-53-0-1 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

№ 188 |

13-3-0-1 (II/33) – lament |

|

№ 192 |

13-32 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

№ 194 |

12-38-9 – bagpipe-swineherd, 13-28 – bagpipe-swineherd songs |

|

№ 196 |

10-3 – fifth-shifting, 11-8-0-1 – fifth-shifting, 11-18 – fifth-shifting, 12-1 – fifth-shifting |

|

Class 12 |

Jir tunes |

|

№ 201 |

10-21-0-1 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

№ 202 |

10-1 – fifth-shifting |

|

№ 204 |

10-36-1 – rising wide-ranged, 12-44 – rising wide-ranged, 12-51 – rising wide-ranged tunes |

|

№ 205 |

11-91 – rising wide-ranged tunes |

|

№ 206 |

18-329 – rising wide-ranged, 18-351 – rising wide-ranged, 18-352 – rising wide-ranged tunes |

|

№ 209 |

15-10 – rising wide-ranged |

|

№ 211 |

12-52 – rising wide-ranged |

|

№ 221 |

18-81 – shepherd’s song |

|

№ 223 |

12-37-0-1 – bagpipe-swineherd tunes |

|

№ 233 |

12-33-5-1 – bagpipe-swineherd |

|

№ 240 |

10-33 – rising broad-ranged tunes |

|

№ 246 |

12-22 (II/16) – lament |

|

№ 248 |

17-8-1 – fifth-shifting |

|

№ 255 |

10-32-0-1 – rising wide-ranged tunes |

|

№ 256 |

18-271 – bagpipe-swineherd |

|

№ 258 |

17-8-1 – fifth-shifting |

|

Class 13 |

Four long lines in a recursive structure |

|

№ 279 |

18-347 – rising wide-ranged tunes and some new-style tunes |

|

№ 281 |

10-36-1 – rising wide-ranged, 11-92 – rising broad-ranged tunes |

17 For connections between laments of diverse Turkic peoples, see Sipos (2000, 1994, 2001 and 2006).

18 On the psalmodic tunes of Turkic groups, see Sipos (1994, 2000, 2001 and 2006).

19 There are many among the new narrow-ranged tunes.

20 The Hungarian material includes many tunes with 1(1)x cadences, especially among the bagpipe-swineherd tunes.